Series: Oh Say Can You See? V: The American Way

Entry 6:

You’ll Find That You’re in the Rotogravure

(This is the sixth entry in a series on The American Way. Be sure to start with Entry 1 in order to understand the following material in context.)

Earlier entries in this series introduced “The Father of Spin,” Edward L. Bernays.

Eddie was the man who coined—and embodied himself—the title of Public Relations Expert early in the last century for well-paid consultants to businesses, who go far beyond just “advertising” a specific widget. They use methods of persuasion (often hidden) to “sell” industries, companies, product lines, ideas…even politicians and wars…to the public.

Eddie was the man who coined—and embodied himself—the title of Public Relations Expert early in the last century for well-paid consultants to businesses, who go far beyond just “advertising” a specific widget. They use methods of persuasion (often hidden) to “sell” industries, companies, product lines, ideas…even politicians and wars…to the public.

In the most recent entry, we saw how Eddie crafted a campaign in 1928 for the American Tobacco Company (ATC) to most effectively convince the public to “reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet.”

With that campaign, he didn’t just sell the Lucky Strike cigarette, he sold the whole idea of smoking being useful to women in particular to keep a “healthy, attractive figure.” And this wasn’t done just through ads showing skinny ladies smoking—Eddie always went above and beyond. For that campaign, he persuaded hotels to add cigarettes to their dessert lists. He had a series of menus widely distributed that had been prepared by an editor of House and Garden magazine. It included the advice to “reach for a cigarette instead of dessert.” He solicited testimonials from doctors, debutantes, actors, athletes…even aviatrix Amelia Earhart.

With that campaign, he didn’t just sell the Lucky Strike cigarette, he sold the whole idea of smoking being useful to women in particular to keep a “healthy, attractive figure.” And this wasn’t done just through ads showing skinny ladies smoking—Eddie always went above and beyond. For that campaign, he persuaded hotels to add cigarettes to their dessert lists. He had a series of menus widely distributed that had been prepared by an editor of House and Garden magazine. It included the advice to “reach for a cigarette instead of dessert.” He solicited testimonials from doctors, debutantes, actors, athletes…even aviatrix Amelia Earhart.

But Eddie wasn’t through helping the ATC. George Washington Hill, head of the ATC, had hired Eddie to spin that particular idea. When it succeeded even beyond expectations, Hill was ready for more of Eddie’s wizardry.

Hill loved the way Bernays used the anti-sweets campaign to promote Luckies, but that only whetted his appetite to crack the female market. So early in 1929 he summoned Bernays and demanded, “How can we get women to smoke on the street? They’re smoking indoors. But, damn it, if they spend half the time outdoors and we can get ‘em to smoke outdoors, we’ll damn near double our female market. Do something. Act!”

Bernays understood they were up against a social taboo that cast doubt on the character of women who smoked, but he wasn’t sure of the basis of the inhibition or how it could be overcome. So he got Hill to agree to pay for a consultation with Dr. A. A. Brill, a psychoanalyst and disciple of Bernays’s uncle, Dr. Sigmund Freud. “It is perfectly normal for women to want to smoke cigarettes,” Brill advised. “The emancipation of women has suppressed many of their feminine desires. More women now do the same work as men do. Many women bear no children; those who do bear have fewer children. Feminine traits are masked. Cigarettes, which are equated with men, become torches of freedom.” [Larry Tye, The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays and The Birth of Public Relations. Unless otherwise noted, all further quotes in this entry are from this book.]

It had taken women almost 150 years from the time of the Declaration of Independence to even get the right to vote. The 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, less than a decade before this current story about Eddie begins. Women’s rights and equality of opportunity with men were still very hot topics in US society. And Eddie was always ready to use the latest trends and hot topics to bolster sales for his clients. He was also always ready to use the insights of his Uncle Siggy’s psychoanalytic theories.

And thus Eddie began his scheming.

Eddie particularly favored choreographing public spectacles as part of his methods. And he came up with a splendiferous one for this project. He would insert his own sideshow into the wildly popular New York Easter Parade.

From the 1880s through the 1950s, New York’s Easter parade was one of the main cultural expressions of Easter in the United States. It was one of the fundamental ways that Easter was identified and celebrated.

The seeds of the parade were sown in New York’s highly ornamented churches—Gothic buildings such as Trinity Episcopal Church, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church. In the mid-19th century, these and other churches began decorating their sanctuaries with Easter flowers. The new practice was resisted by traditionalists, but was generally well received. As the practice expanded, the floral displays grew ever more elaborate, and soon became defining examples of style, taste, abundance, and novelty.

Those who attended the churches incorporated these values into their dress. In 1873, a newspaper report about Easter at Christ Church said “More than half the congregation were ladies, who displayed all the gorgeous and marvelous articles of dress,… and the appearance of the body of the church thus vied in effect and magnificence with the pleasant and tasteful array of flowers which decorated the chancel.”

…By the 1880s, the Easter parade had become a vast spectacle of fashion and religious observance, famous in New York and around the country. It was an after-church cultural event for the well-to-do—decked out in new and fashionable clothing, they would stroll from their own church to others to see the impressive flowers (and to be seen by their fellow strollers). People from the poorer and middle classes would observe the parade to learn the latest trends in fashion.

By 1890, the annual procession held an important place on New York’s calendar of festivities and had taken on its enduring designation as “the Easter parade.”

As the parade and the holiday together became more important, dry goods merchants and milliners publicized them in the promotion of their wares. Advertisements of the day linked an endless array of merchandise to Easter and the Easter parade. In 1875, Easter had been invisible on the commercial scene. By 1900, it was as important in retailing as the Christmas season is today. [Wiki: Easter Parade]

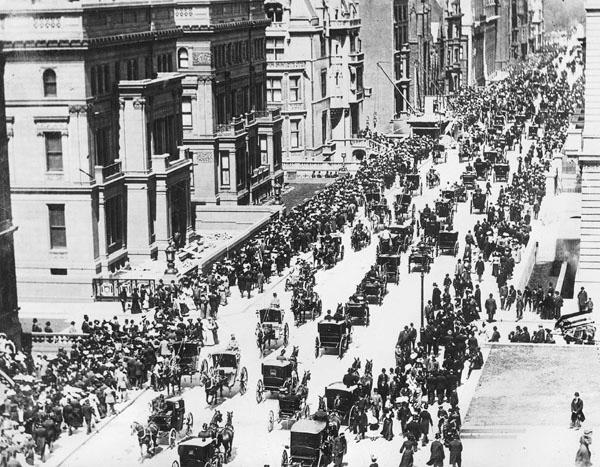

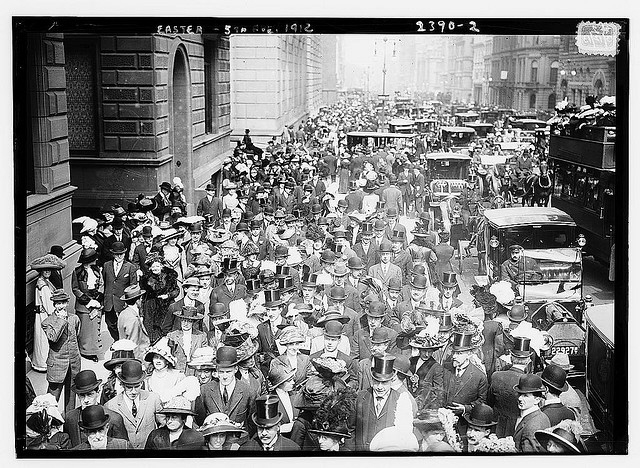

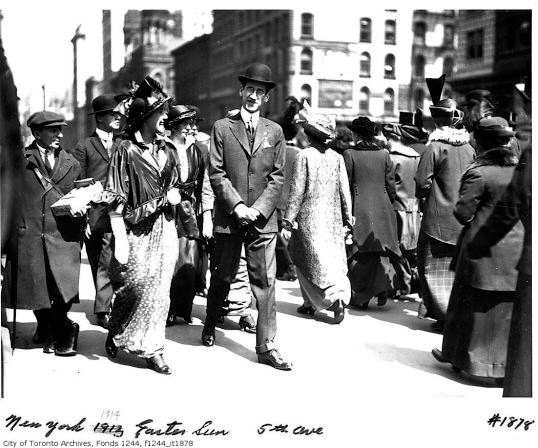

It was estimated in 1947 that over a million people gathered to gawk at the finery of those in the parade. (The parade’s popularity is almost gone now…in 2008, there were about 30,000.) Here are a few pics to help you get a feel for how influential this parade was.

1900:

1912

1914

Eddie Bernays was a resident of New York City, and intimately familiar with the popularity of the Parade. He was also intimately familiar with the popularity and power of the rotogravure, the pictorial “Sunday Supplement” of newspapers of the time. (The term rotogravure refers to a certain type of printing process that uses a rotary printing press.)

Eddie Bernays was a resident of New York City, and intimately familiar with the popularity of the Parade. He was also intimately familiar with the popularity and power of the rotogravure, the pictorial “Sunday Supplement” of newspapers of the time. (The term rotogravure refers to a certain type of printing process that uses a rotary printing press.)

Once a staple of newspaper photo features, the rotogravure process is still used for commercial printing of magazines, postcards, and corrugated (cardboard) product packaging.

…In the 1930s–1960s, newspapers published relatively few photographs and instead many newspapers published separate rotogravure sections in their Sunday editions. These sections were devoted to photographs and identifying captions, not news stories.

Here’s a sample page of a rotogravure section from a Syracuse, NY, paper in 1930. That’s NY Governor Franklin Roosevelt—a paraplegic polio victim himself—visiting young polio victims.

Irving Berlin’s song “Easter Parade” specifically refers to these sections in the lines “the photographers will snap us, and you’ll find that you’re in the rotogravure”.

Here are Judy Garland and Fred Astaire in a fictionalized version of the 1912 New York Easter Parade, from the 1948 movie Easter Parade. Their movie had actually been constructed around the song, which Berlin had originally written for a 1933 Broadway musical revue, As Thousands Cheer. It had also been sung earlier by Bing Crosby in his 1942 movie, Holiday Inn.

And the song “Hooray for Hollywood” contains the line “…armed with photos from local rotos” referring to young actresses hoping to make it in the movie industry.

In 1932 a George Gallup “Survey of Reader Interest in Various Sections of Sunday Newspapers to Determine the Relative Value of Rotogravure as an Advertising Medium” found that these special rotogravures were the most widely read sections of the paper and that advertisements there were three times more likely to be seen by readers than in any other section. [Wiki: Rotogravure ]

If Bernays wanted to spread his message widely, the New York Easter Parade was the place to stage a “scene” to attract reporters and photographers, and the rotogravures of the American press would provide the avenue to spread those photos from coast to coast.

As usual, Eddie hid in the shadows while pulling the strings, providing himself plausible deniability. These staged events were always supposed to “appear” to be grass-roots, virtually spontaneous activities springing from the intentions of just “common folks.” In this case, Eddie contacted a friend who worked at Vogue magazine and got addresses for thirty debutantes. He then sent a telegram to each, signed by his secretary Bertha Hunt. The telegram read, “In the interests of equality of the sexes and to fight another sex taboo I and other young women will light another torch of freedom by smoking cigarettes while strolling on Fifth Avenue Easter Sunday.We are doing this to combat the silly prejudice that the cigarette is suitable for the home, the restaurant, the taxicab, the theater lobby but never, no, never for the sidewalk. Women smokers and their escorts will stroll from Forty-Eighth Street to Fifty-Fourth Street on Fifth Avenue between Eleven-Thirty and One O’Clock.”

Eddie also placed an ad with similar wording in New York newspapers, signed by Ruth Hale, “a leading feminist and wife of New York World columnist Heywood Broun,” announcing what sounded like just the jolly plan of some free-spirited young women. But of course, it was anything but a casual whim.

The script for the parade was outlined in revealing detail in a memo from Bernays’s office. The object of the event, it explained, would be to generate “stories that for the first time women have smoked openly on the street. These will take care of themselves, as legitimate news, if the staging is rightly done.

Undoubtedly after the stories and pictures have appeared, there will be protests from non-smokers and believers in ‘Heaven, home and mother.’ These should be watched for and answered in the same papers.”

The memo also discussed prominent churches the parade would pass, and from which it would like marchers to join up, including Saint Thomas’s, Saint Patrick’s, and “the Baptist church where John D. Rockefeller attends.” What kind of marchers would be best? “Because it should appear as news with no division of the publicity, actresses should be definitely out. On the other hand, if young women who stand for feminism— someone from the Women’s Party, say— could be secured, the fact that the movement would be advertised too, would not be bad.… While they should be goodlooking, they should not look too ‘model-y.’ Three for each church covered should be sufficient. Of course they are not to smoke simply as they come down the church steps. They are to join in the Easter parade, puffing away.”

As usual, Eddie managed all this behind the scenes as if it was a military campaign!

The memo made it clear that not much would be left to chance: “On Monday of Holy Week, the women should be definitely decided upon. On the afternoon of Good Friday, they should be in this office, by appointment, and given their final instructions. They should [be] told where and when they are to be on duty Easter morning and furnished with Lucky Strikes. As the fashionable churches are crowded on Easter, they must be impressed with the necessity of going early. ‘Business’ must be worked out as if by a theatrical director, as for example: one woman seeing another smoke, opens her purse, finds cigs but no matches, asks the other for a light. At least some of the women should have men with them.”

But what if all this took the newspaper reporters of New York by surprise so much that they couldn’t get news photographers in place in time to get good pics of all the scandalous activity?

Finally, there was the matter of ensuring that the march would be preserved for posterity: “We should have a photographer to take pictures for use later in the roto sections, to guard against the possibility that the news photographers do not get good pictures for this purpose.”

And all of the meticulous planning paid off.

The actual march went off more smoothly than even its scriptwriters imagined. Ten young women turned out, marching down Fifth Avenue with their lighted “torches of freedom,” and the newspapers loved it. Two-column pictures showed elegant ladies, with floppy hats and fur-trimmed coats, cigarettes held self-consciously by their sides, as they paraded down the wide boulevard.

And indeed the press all across the country took gleeful interest in the spectacle.

Dispatches ran the next day, generally on page one, in papers from Fremont, Nebraska, to Portland, Oregon, to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Typical was this one from the United Press: “Just as Miss Federica Freylinghusen, conspicuous in a tailored outfit of dark grey, pushed her way thru the jam in front of St. Patrick’s, Miss Bertha Hunt and six colleagues struck another blow in behalf of the liberty of women. Down Fifth Avenue they strolled, puffing at cigarettes.

Miss Hunt issued the following communiqué from the smoke-clouded battlefield: ‘I hope that we have started something and that these torches of freedom, with no particular brand favored, will smash the discriminatory taboo on cigarettes for women and that our sex will go on breaking down all discriminations.’”

But was it just a gimmick for people to gawk at? Did it actually affect the actions of others?

Go on they did. During the following days women were reported to be taking to the streets, lighted cigarettes in hand, in Boston and Detroit, Wheeling and San Francisco. Women’s clubs, meanwhile, were enraged by the spectacle, and for weeks afterward editorial writers churned out withering prose, pro and con. “Thumbs down,” said the News in Everett, Massachusetts, while John A. Schaffer, editor and publisher of the Chicago Evening Post, the Indianapolis Star, the Terre Haute Star, and the Muncie Star, agreed that “it is always a regret to me to see women adopt the coarser attitudes and habits of men.” But the headline in the Ventura, California, Star, “Swats Another Taboo,” suggested the march may have achieved its aim, and a few weeks later Broadway theaters created a stir by admitting women to what had been men-only smoking rooms.

Eddie’s ego was big enough that he no doubt expected to get good results from his efforts. But perhaps even he was surprised at just how easily it could be pulled off, and how widely and quickly it could spread.

The uproar he’d touched off proved enlightening to Bernays. “Age-old customs, I learned, could be broken down by a dramatic appeal, disseminated by the network of media,” he wrote in his memoirs. “Of course the taboo was not destroyed completely. But a beginning had been made.”

Never underestimate the powers of the Hidden Persuaders! Nor how long ago they were already busily at work playing with people’s emotions. I remind you…this wasn’t done in 2013, with the aid of the millions of ever-vigilant cell-phone-camera-equipped, man-on-the-street i-Reporters of the nation, and with computers and the Internet Superhighway as the avenue through which to spread a story instantaneously throughout the land. It was done “Old School,” with telegrams, hardcopy paper pages, and reporters …using rotary dial phones to call in their stories…

…which a secretary would then peck out on a clunky old typewriter like this 1929 Underwood…

And yet the strange little project, master-minded by one timid-looking little fellow behind a curtain, literally did catch the imagination of the nation overnight. People worry these days that the era of “Big Brother” and his persuasive methods are upon us. Nah…they’ve been around for over a century.

The Torches of Freedom campaign remains a classic in the world of public relations, one still cited in classrooms and boardrooms as an example of ballyhoo at its most brilliant and, more important, of creative analysis of social symbols and how they can be manipulated.

Continue on to the next entry in this series for another peek behind the curtain of the manipulators and intimidators:

Pingback: Oh Say Can You See? V: The American Way: Part 6 | Currently StaRRing …